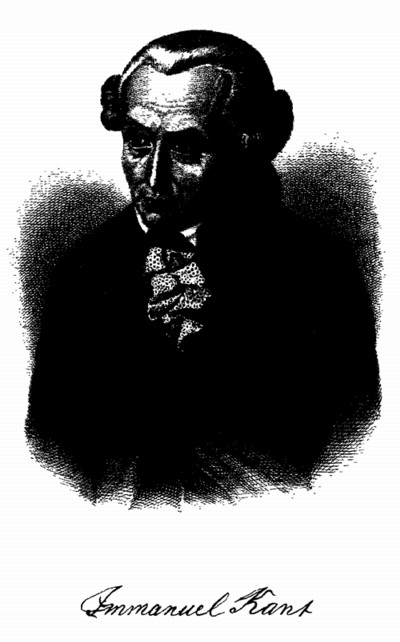

Immanuel Kant, Kant’s Prolegomena and Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science. [1783]

Edition used:

Kant’s Prolegomena and Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, trans. with a Biography and Introduction by Ernest Belfort Bax (2nd revised edition) (London: George Bell and Sons, 1891).

- Author: Immanuel Kant

- Translator: Ernest Belfort Bax

Immanuel Kant, Kant’s Prolegomena and Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, trans. with a Biography and Introduction by Ernest Belfort Bax (2nd revised edition) (London: George Bell and Sons, 1891).

Accessed from http://oll.libertyfund.org/title/361 on 2013-07-31

About Liberty Fund:

Liberty Fund, Inc. is a private, educational foundation established to encourage the study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals.

Copyright information:

The text is in the public domain.

Fair use statement:

This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit.

Table of Contents

Hide TOC- Preface.

- A Biography of Kant With Some Remarks on His Position In Philosophy.

- Kant’s Position In Philosophy.

- Prolegomena to Every Future System of Metaphysics Which Can Claim to Rank As Science.

- Introduction.

- Introductory Remarks on the Speciality of All Metaphysical Knowledge.

- The General Question of the Prolegomena. Is Metaphysics Possible At All?

- General Question. How Is Knowledge Possible From Pure Reason?

- The Transcendental Main Question—first Part. How Is Pure Mathematics Possible?

- The Second Part of the Main Transcendental Problem. How Is Pure Natural Science Possible?

- Appendix to Pure Natural Science. of the System of the Categories.

- The Third Part of the Main Transcendental Problem.

- Conclusion. on the Determination of the Boundary of the Pure Reason.

- Solution of the General Problem of the Prolegomena. How Is Metaphysics Possible As Science.

- Appendix.

- The Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science.

- Preface.

- First Division.: Metaphysical Foundations of Phoronomy.

- Metaphysical Foundations of Dynamics.

- Metaphysical Foundations of Mechanics.

- Fourth Division.: Metaphysical Foundations of Phenomenology.

PREFACE.

The growing interest taken in philosophy in this country has led to the issue of the present volume of “Bohn’s Philosophical Library,” containing the presentation for the first time to the British public of one work, important alike to the votary of physical science and of philosophy, and an entirely fresh translation of another which is absolutely indispensable at least to the philosophical student of Kant.

Only two English translations of the “Prolegomena” have hitherto been published. The first (a very bad one), by John Richardson, appeared in 1818, and has been out of print for many years past. The second (based on the last-mentioned) forms one of the volumes in Professor Mahaffy’s series entitled, “Kant’s Critical Philosophy for English Readers,” and while avowedly a somewhat free rendering, conveys the sense of the original fairly well, but its relatively high price places it beyond the reach of many persons. The present translation aims at giving, as far as possible, the ipsissima verba of Kant. No attempt has been made to convert the cumbrous German of the original into elegant English. Even the form and length of the sentences have been retained wherever possible, as it has been thought preferable to place before the reader Kant himself, with all his lack of literary polish, rather than any mere paraphrase of Kant.

Words not contained in the original are indicated by square brackets, as a distinction from Kant’s own, only too numerous, bracketed clauses. The practice of invariably retaining one particular English equivalent for a German word irrespective of usage has not been adhered to, the same word being variously translated according to circumstances. Vorstellung (in a philosophical sense) has been rendered by “presentation,” and for the rest the currently recognised equivalents of the German philosophical expressions have been for the most part adhered to, though some slight deviations from traditional precedent will be observed by the careful reader.

It may be worth while to mention that Dr. Vaihinger, of Strasburg, has indicated (“Philosophische Monatshefte,” XV., pp. 321–332 and 513–532) a remarkable confusion in the paragraphing near the commencement of the Prolegomena. For the conclusive arguments which he adduces in support of his alteration, the reader must be referred to the articles themselves, space only admitting of the result of his investigations being given. This (we quote his own words) is as follows:—“The printer has erroneously introduced the paragraph [p. 18 of present volume] ‘The essential feature distinguishing pure mathematical knowledge,’ &c., down to the sentence on p. 20, concluding with the words ‘make up the essential content of metaphysics,’ into § 4, whereas it directly and with strict logic follows the conclusion of § 2, p. 16, ‘but by means of an added intuition upon its subject.’ ” Dr. Vaihinger instances sundry misconceptions that have arisen from what was probably an accidental misplacement in the leaves of the manuscript.*

The Prolegomena were designed by Kant as an abstract of the Critique, the idea being the presentation in a succinct form of the leading positions of the larger work. In this we venture to think Kant was hardly successful. He labours here, as in the Critique, under the disadvantage of the pioneer, that of not fully grasping the import of his own discovery. While in the Critique the really salient points of the system—those which alone furnish a key to the whole—are overlaid by a mass of comparatively unessential superstructure, and instead of being emphasised and expounded in their entirety at the commencement, in most cases have to be discovered and inferred from detached passages and sections scattered throughout the book; in the Prolegomena they seem purposely left in the background. The real cornerstone of the Critique (although Kant did not see it), the deduction of the categories, is omitted altogether.

Kant, in writing the Prolegomena, seems indeed to have had in his mind the same essentially negative view of the scope of his system we find expressed in the note in the Anfangsgründe on pp. 144 et seq. of present volume. If his object was simply to demolish dogmatic metaphysics, by a limitation of speculation to experience, as its subject-matter, the Prolegomena are admirable, since they are in many respects clearer than the Critique. But if, on the other hand, this negative side of Kant’s labours was only a clearing of the ground for the original and constructive portion of his work, the formulation and attempted solution of the problem, “How is experience itself possible?” then we find in the Prolegomena the shortcomings of the Critique in an exaggerated form.

The basis of this latter side of Kant’s system, it cannot be too much insisted upon, is the conception of (I.) consciousness-in-general or pure consciousness, as opposed to the consciousness or experience given directly through the individual mind, the object of empirical psychology; (II.) the unity of apperception, which indicates the first moment of the differentiation of form from matter (an important antithesis that Kant rehabilitated), that is, the first moment of the possibility of consciousness; and (III.) finally the immanent noumenon or fundamental agency of which consciousness itself with all its momenta, is the determination. This last, although tacitly assumed throughout, and frequently referred to in terms of psychology as the “mind,” (das Gemüth), it was reserved for Kant’s successors to definitively fix.

Perhaps the greatest service of Kant is the differentiation of the consciousness-in-general, which is constitutive of reality, or in other words, is productive of the synthesis of experience, from the psychological consciousness or mind of the individual qua individual, which is merely reproductive of this synthesis. This is Kant’s great advance upon Berkeley and Hume, who, trained in the psychological school of Locke, failed to distinguish between metaphysics, or theory of knowledge—i.e., the science of the possibility of synthetic or productive experience, in other words, of consciousness-in-general—and psychology, the science of the reproduction of this synthesis in the experience of the individual. Berkeley demolished the scholastic substance or material substratum apart from consciousness, but having done so was confronted with the paradox that he had resolved objective reality into subjective ideality. That this absurdity was only apparent he felt, but was unable to point out where lay the source of the appearance for the reason above stated, namely, his inability to distinguish between consciousness quâ consciousness, and its reflection in mind.

The Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaft has never before appeared in an English form. The same remarks, as regards the aim and character of the translation, will apply to this work as to the Prolegomena. I must ask, however, for some indulgence in this case for an occasional barbarism (e.g., “a plurality of the real, outside one another,”) owing to the difficulty of rendering Kant’s meaning adequately in all cases by good English. In the Anfangsgründe Kant seems to have surpassed himself in clumsiness and obscurity of style. In several sentences the verb is wanting, and others by the omission of a negative particle or a similar carelessness, make precisely the reverse sense to that, judging by the context, obviously intended.

The treatise in question is of especial interest in relation to modern speculation on the data of physical science, and particularly as to the ultimate constitution of matter, and may be profitably studied in conjunction with such works as Professor Wurtz’s, “Atomic Theory,” Mr. Stallo’s “Concepts of Modern Physics,” and Mr. Herbert Spencer’s “First Principles.” Written in 1786, just one year before the publication of the second edition of the “Critique,” it belongs to the maturest period of Kant’s philosophical activity. It may be of interest to allude to the fact that since the introductory portion of the present volume was in the press the manuscript treatise of Kant entitled, Uebergang von den Metaphysischen Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaft zur Physik, “Transition from the Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science to Physics,” has been disinterred and published in the Altpreussische Monatshefte for the year 1882. It should be added that the edition used, both in the case of the Prolegomena and the Anfangsgründe, is that of the collected works by Kirchmann, which, although not without flaw, is probably on the whole the most accurate we possess.

A short biographical sketch of Kant has been supplied by way of introduction to the volume. This is founded chiefly on the old sources, Wasianski, Borowski, Jachmann, Reicke. Schubert, &c. The biography is supplemented by a chapter dealing with Kant’s position in the evolution of thought, which, although necessarily to a large extent a mere bald outline, it has been thought might possibly prove suggestive to students, and stimulative to independent research in some of the directions indicated.

[Back to Table of Contents]A BIOGRAPHY OF KANT

WITH SOME REMARKS on HIS POSITION IN PHILOSOPHY.

Before entering upon our biography of Kant, it may be instructive to take a rapid survey of the condition of Königsberg and German society in the early part of the 18th century. Prussia was at this time under the iron rule of Frederick William I. of tall-hussar notoriety. Since the independence of the country had been established, the trade and importance of Königsberg had advanced with rapid strides. Every spring brought a stream of vessels from England, Holland, Russia, Poland, and other countries. The Baltic town was also the centre of such intellectual life and activity as then existed in Prussia. on more than one occasion it had even offered strenuous resistance to the ordinances of the autocratic monarch himself. In this way a strongly-cemented municipal feeling had been formed which affected all classes of citizens. Various causes had contributed to swell the number of the inhabitants of Königsberg. The fact that the elevation of Prussia to a kingdom had been formally proclaimed from there had given it a certain patriotic importance of its own. But what probably more than anything else helped the rapid increase of the city’s population, was its having been neutral territory during a long war. The university (founded in 1553) especially benefited by this circumstance. Students flocked in from various sides, from Poland and the Baltic districts on the one hand, and from Pomerania, Silesia, and East Prussia generally, on the other. Several important municipal schools were, moreover, opened about this time.

The state of general culture in Germany during the first half of the century was very much what the close of the preceding century had left it. The era of modern German literature had not commenced. The seventh-magnitude poets and dramatists whose names are preserved in the pages of Goethe’s Dichtung und Wahrheit were the oracles of public taste; an array of equally obscure philosophasters dominated the universities, while philosophy, together with all the more solid branches of Literature, was conducted in Latin, according to true mediæval fashion. Some few jurists and philologists alone, belonging to this period, attained to a more than ephemeral reputation. Germany had not as yet recovered from the blighting results of the Thirty Years’ War, which effectually destroyed the germs of the awakening culture of the Reformation period. But in spite of this unpromising state of affairs, signs of an imminent revival were not wanting. The brilliant and cosmopolitan genius of Leibnitz had prepared the way for the first essentially German philosopher, Christian Wolff. Wolff, besides being the first thinker to write in German, has the credit of having staunchly, and at times to his own cost, adhered to his master’s resistance to the claims of authority, as such, and this fact may be set against the intrinsic worthlessness of his philosophy. The most interesting point in connection with Wolff, is, however, his having been the forerunner of Kant. In general literature, towards the middle of the century, a similar revival is noticeable, the glow of dawn before the rising of the sun of Goethe and his congeners. The time will perhaps be best appreciated in its intellectual aspect when we recall the fact that the popular essayist Thomasius, the precursor of the later Aufklärung writers, died as late as 1728, and that he was a main instrument in exploding the belief in witchcraft among the educated classes, and in abolishing the laws directed against it, as well as a determined, and, to a large extent, successful opponent of the practice of judicial torture.

But the most important influence at this period dominant in North Germany, was not so much embodied in literature as in the social life of the people. We refer to the “Pietism” which then reigned, to a greater or less extent, in well-nigh every German home, and which formed such a marked feature in the early life of the subject of the present biographical sketch.

Such were the social conditions of Germany when the worthy saddler, Johann Georg Cant, was carrying on his handicraft in the Sadlergasse of Königsberg, learning to labour and to wait for those better days which, alas! he was never destined to see reward his labour. Johann Georg, in fact, though an upright and excellent man, appears to have been more esteemed by his fellow townsmen for his personal character than his saddle-making abilities. In spite of rigid economy, he never compassed more than very “moderate” circumstances, even according to the standard of the German Kleinbürger—and he not the Kleinbürger of to-day, but of the 18th century—while at times, it seems, he had a difficulty in making the proverbial two ends meet. Though originally of Scotch extraction, the Cant family had been settled for some generations in the Baltic province, at the time of which we speak. It was on November 13th, 1715, that Johann Georg Cant was united, in the cathedral church of the city, to Anna Regina Reuter, if we may judge by the name, a genuine daughter of the Baltic shores. As is not unusual with persons in the position of the elder Cant, a large family was the issue of this marriage, eleven children in all, four sons and seven daughters. Of these six died in infancy.

Immanuel, the fourth child and third but eldest surviving son, was born on April 22nd, 1724. His only brother, Johann Heinrich Cant, the youngest child, and eleven years his junior, after passing many years as private tutor in various aristocratic families, ultimately obtained the rectorate of Mitau and afterwards of Rahden, two country districts, the latter of which he held till his death a few years before that of his elder brother. Of the three sisters, Regina Dorothea, Maria Elisabeth, and Catherina Barbara, the eldest died unmarried, while the two younger developed into excellent housewives and mothers of families of the true German Bürgerin type, the youngest of all outliving Immanuel. Kant, throughout his life, acted as the benefactor of his relations and their children, who inherited the bulk of his property.

Frau Cant died when her son Immanuel was thirteen years old. It is related that her death was caused by a circumstance aptly illustrating her goodness of heart. A female friend to whom she was much attached, having been deserted by her betrothed, was attacked by a fever induced by mental excitement. Frau Cant, who zealously watched by her bedside, on one occasion endeavoured vainly to induce her to take her medicine, which she refused, even when the spoon containing it was pressed to her lips. As a last resource, her friend, thinking to overcome her repugnance by example, swallowed the mixture herself. No sooner had she done this than she was seized with a nervous horror, intensified by the fancy that she saw on the patient’s body symptoms of spotted typhus. She at once gave herself up for lost, fell ill of a similar fever the same day, and in a few days after expired. Kant, who was devotedly attached to his mother, could never speak of her, even in his later years, without betraying the deepest emotion.

Pietism reigned supreme in the house in the Sadlergasse, and Kant’s mother was especially addicted to it. Kant spoke of her as possessed of an inward peace and cheerfulness, capable of being disturbed by no outward circumstances. He was fond of relating how, in a trade dispute, in which his father was engaged, and had suffered considerable loss, she would speak with the greatest consideration of the opponent party, and express the most implicit trust in Providence. In later life the impression of his mother seems to have been more vivid than of his father. He would tell how he used to accompany her in long country walks, of her zeal in directing his attention to the various phenomena of Nature, and in offering such explanations as lay within her reach, with their invariable epilogue on the wisdom and goodness of the Creator. It would appear as though Immanuel had been her favourite child. Besides receiving his general instruction in an institution famed for the pietism of its management, and diligently attending the church in connection with it, he had to be present at the prayer meetings of Professor Schultz, his mother’s chief spiritual adviser, who pressed these devotional exercises with emphasis on the attention of the “spiritually minded” among his congregation. These meetings led to a more intimate connection with Schultz, which resulted in bringing about the first epoch in the young Immanuel’s career. Schultz had been always well disposed towards the Kants, supporting them in various ways; such as sending them firewood in the winter carriage paid, etc. He was also a frequent guest at their house. In this way various occasions for observing the rising abilities of the elder son presented themselves, and in consequence he earnestly advised his being allowed to devote himself to studious pursuits. This was readily agreed to, his mother joyfully anticipating the realisation of her long cherished wish that he should enter the church. She, however, died under the circumstances narrated, before he had completed his school education.

The irony of fate is certainly in few cases more strikingly manifested than in Kant’s. Nurtured in the straitest sect of the orthodox creed of his day, trained doubtless at great sacrifices on the part of his parents that he might become an adequate exponent of that creed, he was yet destined to prove the most tremendous disintegrating force of modern times, springing intellectual mines, causing old creeds and formulas to fall in (so to speak) of their own weight. In Kant, philosophy and science became definitely emancipated from theology. A parallel involuntarily suggests itself between the respective attitudes towards religious beliefs of Kant and his elder contemporary, Voltaire, the one the subject, and the other the friend, of Frederick the Great. In the first we have the type of 19th century, in the second of 18th century thought. Both were alike in the immense range of their culture and interests; both were alike in the revolutionary character of their work. But, besides the difference which, of necessity, distinguishes the mere man of letters from the philosopher in his mode of thought and treatment, they differ as representing two diverse phases of the great intellectual movement of modern times. The attitude of 18th century thought towards current beliefs, where it was not one of ironical servility, was one of direct and uncompromising hostility; in fact, paradoxical as it may sound, we not unfrequently see the two attitudes combined as in the famous 15th and 16th chapters of Gibbon. What is now known as the historical point of view is, of course, conspicuous by its absence. In no writer is this more noticeable than in the author of the Dictionnaire Philosophique. In Kant, on the contrary, may be discerned the germs of the historical method which explains rather than attacks dogmas, and of the extra-theological (in contradistinction to anti-theological) attitude of modern science, which, wherever possible, ignores points of direct conflict by disregarding dogma as altogether outside its sphere. This later mode of thought, there can be no doubt, had its origin in Kant’s distinction of the speculative and practical reason, although adopted by many who would repudiate this distinction. The world of philosophy and science has more and more tended in the 19th century to exclude all direct theological considerations, whether apologetic or polemical, from its pale. There can, we think, be little doubt that the habit of thought inaugurated by the Königsberg thinker, in spite of its reverent attitude towards, at least, the fundamental conceptions of theology, has been an incomparably more potent factor in current disintegration, at least outside the Latin countries, than the direct onslaughts of Voltaire and the French thinkers of the 18th century. The tendency at present is, indeed, to exaggerate the historical method, or at least to draw from it conclusions scarcely warranted. The sense of historic continuity, and of evolution, leads many thinkers to ignore the significance of epoch-making events and sudden changes, or of voluntarily-directed action in human affairs.

But to return to our young schoolboy, as yet in ignorance of the destiny the fates had in store for him, and anticipating, in all probability, as the farthest goal of his studies no more than the Pfarrerthum of some country town or village. Kant was never largely communicative on the subject of his boyhood, but the couple of stories preserved may as well be reproduced. on one occasion, when on his way to school, he was allured by some young friends he met, into taking part in a game. This necessitated his laying down his books on the road. The game ended, he rushed off to make up for lost time and arrived at school just in time to see the class commence, when, to his consternation, the fact of his being without books suddenly dawned upon him. With the greatest composure he nevertheless confessed to the delinquency, and submitted to the inevitable punishment. Another time he was crossing a brook on the trunk of a tree which had been thrown or had fallen over it. He had only advanced a few steps when it showed alarming symptoms of rolling under his feet. Nothing daunted, our Immanuel fixed his eyes on a point on the opposite side, and, without moving them, dashed straight at it, by this means reaching terra firma in safety.

At Michaelmas 1740, in his seventeenth year, Kant entered the university of his native town as a student in theology, a faculty which appears soon to have been relinquished. The immediate occasion of this, was that another student had been preferred to a scholarship in the Domschule for which Kant had been a candidate. But we may suppose that, even at this early period of his career, the foregoing was not the only reason. It may be mentioned that Kant preached once or twice during his theological terms in a neighbouring country church in accordance with the custom at that time prevalent in Prussia for younger students to try their powers on country congregations. Philosophy and mathematics were now chosen as his subjects from among the university faculties. The chief and indeed only permanent bias Kant received from his school period was a fondness for the Latin classics, which he studied so thoroughly that, years after, he could recite long passages from memory. It is possible that he might have selected philology as his faculty instead of those actually chosen, but for the fact of its being badly represented in the university at the time. The choice made proved decisive for his whole life. Professor Martin Knutzen, who occupied the chairs of philosophy and mathematics, was a man to stimulate and encourage any latent abilities in the students who attended his lectures, and was, naturally, not long in discerning such in Kant. Kant accordingly obtained every possible assistance in his studies from this academical worthy, who allowed him free access to his own well-stocked library, and introduced him to the works of Newton. Poor Knutzen only lived to see the first result of his praiseworthy endeavours to encourage rising genius, in the shape of Kant’s maiden essay entitled, ‘Reflections on the just Estimation of living Forces.’ In addition to those of Knutzen, Kant attended the lectures of Professor Johann Gottfried Teske on natural science. These two men appear to have been the only teachers in the university whom Kant regarded as having had any material influence in moulding his intellectual character. He spoke of both of them with gratitude and reverence, throughout his whole subsequent life, but made little or no mention of any one else among the professors, although he heard, for some time, Schultz on theology, and Johann Behm on classical literature. Towards the close of his university period, Kant was necessarily confronted with the problem of selecting a carrière. After some hesitation, he decided for the academic profession. Even before the completion of his own studies, he found himself compelled to give lessons at a very inadequate remuneration in classics, mathematics, and physical science. Later, he applied for the humble post of under-tutor in one of the schools attached to the university, which, though a position of sheer drudgery, would have at least secured for him the use of the university library. Fortunately for his future, which must have been seriously compromised by a step entailing the surrender of well-nigh all private study, the vacancy was filled up, probably through influence, by a candidate not likely to feel the loss of it. Just at this time Kant’s father died (March 24th, 1746), a circumstance which threw him completely on his own resources. With a heavy heart he found himself compelled to leave Königsberg, and seek a position as private tutor, finishing his preparation for the university post he hoped ultimately to fill, in his leisure time.

The first family into which he entered in his new capacity was that of a country pastor named Andersch. Thence he removed to the family of a landed proprietor, Von Hulsen of Arensdorf, near Mohrungen, subsequently ennobled by Frederick William III., where he remained for some time, giving great satisfaction and permanently attaching himself to his pupils. one of them subsequently resided with him as boarder, after he had become finally settled in Königsberg. Was it owing to Kant’s influence and instruction in their early life, that the young Von Hulsens were the first among the Prussian feudal lords to voluntarily emancipate their peasants, ensuring them the right to the produce of the land on which they lived and worked?

Kant’s third and last place as tutor was in the family of Count Kayserling of Rautenburg, who however resided most of the year in Königsberg. His wife, the countess, is described as a woman of high culture, and one of the leaders of aristocratic society in the city and its neighbourhood. Kant thus found himself suddenly thrown into the most influential circles of his native town, his genius rapidly placing him in the foremost rank. It was during this time that Kant acquired the high polish of manner and distinguished bearing, for which he was afterwards remarkable among Gelehrten. It is not unlikely, also, to have been about this period that he saw fit to change the initial letter of his name from C to K, a step, it is said, he was led to adopt owing to the perversity of many persons in pronouncing it Tsant. Kant remained nine years in his tutorial capacity, before, owing to the support of a relative named Richter, he was enabled to take his degree in philosophy. one of his examination-essays, de Igne, was rewarded by the acknowledgment of his former teacher Teske, that he himself had learnt much from it. Kant received his doctorate on April 17th, 1755, in the presence of a large number of distinguished persons connected with the town and university. During the same term he defended in public debate the principles of his test-essay Principiorum primorum cognitionis metaphysicæ, the necessary preliminary to the post of lecturer, or Privat-docent. With the winter term of 1755 he commenced lecturing on mathematics and physics, continuing to do so, for ten years, contemporaneously with his philosophical lectures. The latter were based in principle on Wolff, Baumeister, and Baumgarten, though text-books were chiefly used to furnish an order for the exposition of his own thought. Criticism was, of course, at this stage undreamt of, but the originality of the great thinker moulded with its unmistakable impress even the dogmatic metaphysics of his pre-critical days. His fascinating delivery combined with his rich and varied erudition to procure him a large audience. In the dry and cumbrous language of the ‘Critique’ and many other of the later works, it is difficult to detect the humorous and versatile lecturer, full of illustrations drawn from every conceivable source, his own experience of life, no less than from history and science, who charmed the students of Königsberg university, before his fame had reached the outside world. The success of the lectures was so great that constant demands were made for additional courses not contained in the original syllabus.

The first great work of Kant’s appeared almost at the commencement of this period of his academical activity. Kant had just received his license as Privat-docent when he published his ‘General Natural History and Theory of the Heavens,’ one of the most remarkable astronomical works of the century, and which even now may be read with profit. A few months afterwards, the memorable earthquake of Lisbon afforded him the opportunity of exhibiting his research in questions of physical geography. In April 1756, it became necessary for him to undertake another public disputation, as by an ordinance of Frederick the Great three disputations on a printed theme were requisite before a Privat-docent could enter a professorship. To this end he wrote his treatise De Monadologia physica. on the successful issue of the ordeal, Kant applied for the post of extraordinary professor of mathematics and metaphysics, for some little time vacant by the death of his old teacher Martin Knutzen. But the government, busy with war-preparations, and anxious to reduce expenditure, decided to leave the post still unoccupied. Two years subsequently the ordinary professorship in the same departments became vacant, and Kant again applied for the position. The Prussian government had in the meantime (it was during the Seven Years’ War) handed over the province to the Russians, and the Russian governor-general, Nikolaus von Korff, was chief of both the military and civil executive. Kant had as a competitor a Dr. Buck, who was influential in high places, and in spite of his own good recommendations failed to secure the appointment. Continuing his life as Privat-docent, he extended the range of his departments to “philosophy of religion,” anthropology, and physical geography, besides giving special lectures on other subjects. Among Kant’s pupils at this time, was Herder who attended the whole of the courses delivered between the years 1762 and 1764. Kant allowed Herder to attend free of cost, a not insignificant act of generosity when one considers that Kant himself was in circumstances far from “easy” at the time; and we can scarcely absolve the author of the ‘Ideen zur Geschichte der Menschheit” from the charge of ingratitude, for having allowed an adverse criticism of his book to be the cause of the bitterness he subsequently displayed. There can be no doubt, that, great as Herder’s own genius may have been, he owed an immense debt to Kant. A friend of the former relates how careful he was, in noting down every sentence that fell from the philosopher’s lips. once when Kant had discoursed with a more than usual brilliancy—a brilliancy amounting almost to poetic enthusiasm—Herder was so deeply impressed, that on his return home he embodied the substance of the lecture in verse, and the next day handed the manuscript to Kant before the commencement of the class. The latter was so struck with the masterly poetic presentation of his ideas, that he read the poem through to his audience, before his lecture, with a power and emphasis that well rewarded the author for his pains. Herder, in spite of his subsequent quarrel, was constrained, years after, in his ‘Letters on the Improvement of Humanity’ (No. 79) to admit the impressiveness and charm of Kant’s personality, and his rare combination of humour and eloquence with depth of thought. “The same vigorous intelligence,” writes Herder, “with which he tested Leibnitz, Wolff, Baumgarten, Crusius, or Hume and followed out the natural laws established by Newton, Kepler, and other physicists, he brought to bear on Rousseau’s ‘Emile’ and ‘Héloïse’ &c.”

Another noteworthy acquaintance of Kant’s at this time (though the relation between them was not that of master and pupil), was Johann Georg Hamann, the well-known classic and humourist. The characters and paths of the two men were too divergent to admit of anything like a close and lasting friendship. The equable temperament and thoroughness in work of the one, consorted ill with the fitfulness and superficiality of the other. Whether owing to this circumstance or not, it is remarkable that Kant nowhere makes any reference to Hamann, so that, the rooted antipathy of our philosopher to letter-writing preventing any considerable correspondence between them, no evidence (excepting the few letters preserved) remains of their intimacy, if such it was, beyond the testimony of the not too reliable Hamann himself.

But at once the most important and most interesting of all Kant’s friendships remains to be told. I give the story of its origin and nature in the words of Jachmann (pp. 77–82). “The nearest and most intimate friend that Kant had in his life, was the English merchant Green, who died twenty years ago, a man whose peculiar value, and whose important influence on our sage, may be learnt from the description of their friendship. A singular accident, that seemed likely to create a deadly hatred between the two men on their first acquaintance, gave occasion to the closest ties.” “At the time of the Anglo-North American war,* Kant was walking one afternoon in the Danish Garden. He stopped on finding some acquaintances, who were standing in a retired part, talking with some other persons unknown to him. The conversation, in which all present took part, soon turned upon current events. Kant was warmly advocating the American as being the righteous cause, and expressing himself with some bitterness against the English, when suddenly one of the company, springing forward, presented himself before Kant, saying that he was an Englishman, declaring himself and his whole nation outraged by the expressions used, and demanding, at the same time, satisfaction in accordance with the code d’honneur. Kant would not allow his equanimity for a moment to be disturbed by the man’s vehemence, but continued his remarks, expounding the principles on which he based his political views, and the standpoint from which every man, as citizen of the world, irrespective of his patriotism, ought to judge similar events. This was done with such an irresistible eloquence, that Green—for such was the name of the Englishman—filled with astonishment, offered his hand in a friendly manner, acknowledged the nobleness of Kant’s ideas, apologised for his warmth, and after accompanying him in the evening to his house, invited him to a friendly visit. The now deceased merchant Motherby, a partner of Green, was an eye-witness of the occurrence, and has often assured me that Kant seemed to himself and all present, as though inspired by a Divine power, which enchained their hearts for ever to him. Kant and Green thenceforth concluded an intimate friendship, based on knowledge and mutual esteem, a friendship that daily became firmer and closer, and the rupture of which, owing to the early death of Green, occasioned our sage a wound, mitigated indeed by his greatness of soul, but never wholly healed. Kant found in Green a man of wide knowledge, and of so large an understanding, that he himself assured me he never wrote a single sentence in his ‘Critique of the Pure Reason,’ which he had not previously read to Green, and allowed to be criticised by his unbiassed judgment, unpledged as it was to any system. Green was in character a rare man, distinguished by strict integrity and real generosity, but full of the most strange idiosyncrasies; a truly whimsical man, whose days were passed according to a set of inflexible and fanciful rules. I will only give one instance of this. Kant had promised Green one evening to accompany him on the following morning at eight o’clock in a drive. Green, who, as was usual on such occasions, was pacing the room with his watch in his hand a quarter of an hour before the time appointed, at ten minutes put on his hat, at five minutes took his stick, and with the first stroke of the hour opened the carriage door and drove off. He encountered Kant, who was two minutes late, on his way, but did not stop, as this was contrary to the arrangement and his rule. In the society of this gifted, noble-minded, and singular man, Kant found so much nourishment for his intellect and his heart, that he became his constant companion, and for many years they daily spent several hours together. Kant went to him every afternoon, found Green sleeping in an armchair, sat down beside him, put aside his thoughts, and fell asleep also. Then bank director Russmann generally arrived and did likewise, till finally Motherby entered the room at an appointed time, and aroused the company, who entertained each other till seven o’clock with conversation. The little coterie broke up so punctually at seven, that I have often heard the inhabitants of the street say ‘It can’t be seven yet, for professor Kant has not gone past.’ on Saturday, the friends, to whom were added on this occasion the Scotch merchant Hay and some others, assembled to supper, consisting of a frugal cold collation. This friendly intercourse, which fell towards the middle of our sage’s career, had incontestably a decided influence on his character. Green’s death changed Kant’s mode of life so much, that from this time forth, he never again entered an evening gathering, and wholly renounced supper himself. It seemed as though this time, once sacred to his most intimate friendship, he wished to pass in solitude, as a sacrifice to his deceased friend, to the close of his existence.” I have given this interesting narrative of Jachmann at length, as it is characteristic in more ways than one of the philosopher’s character and habits.

In July 1762 the professorship of poetry had become vacant, but was not filled up for some time, in spite of numerous applications, owing to the pre-occupation of the ministry with other matters. Meanwhile Kant’s works and news of his success as lecturer had reached headquarters, and resulted in the following ministerial rescript dated, Berlin, the 5th of August, 1764, signed by the minister of justice, and addressed to the government of the province of Prussia, to be conveyed to the senate of the university of Königsberg. “A certain magister, by name Immanuel Kant, having become known to us by writings displaying thorough scholarship, it is desired to know whether the said Immanuel Kant possesses the requisite acquirements in German and Latin poetry, together with the necessary gifts for teaching the same, and whether he would be inclined to accept this post. on this point you are to obtain information, and thereupon to report accurately; in the event of the said Immanuel Kant either not possessing the necessary acquirements for the occupation of this post, or being indisposed to its acceptance, you are required to bestir yourselves, to propose, in due form, other sufficiently qualified persons.” Kant believed himself to have no special bent for the professorate in question, which would have involved the criticism of all pièces d’occasion, as well as the composition of such on academic festivals, so he at once declined it, at the same time “recommending himself” for a more suitable occasion. Another rescript was issued in reply, to the following effect: “We are none the less most graciously determined to promote the magister, Immanuel Kant, to the use and acceptance of the said academy on another opportunity; and graciously command you accordingly, to notify us, in due obedience, on the manner in which this may be most suitably effected.”

The following year Kant accepted the librarianship of the public library at a salary of sixty-two thalers (£9 6s.) a year, this meagre pittance being the first fixed stipend he obtained from any source. About the same time, his love for natural science led him to undertake the curatorship of a valuable private museum of natural history, and ethnographical objects. This he found himself compelled very soon to relinquish, as the collection being one among the comparatively few “objects of interest” in the city, his presence in showing it became too much in request amongst sightseers. Kant was now living in the house of a bookseller named Kanter, to whose journals the Königsbergischer wöchentliche Nachrichten and the Gelehrte Zeitung, he regularly contributed. In the summer of 1768 Kanter opened “new and extensive” premises, including a room apparently serving the purpose of a reading and writing room for his customers, round the walls of which were hung the portraits of prominent contemporary German scholars. Kant was induced to “sit” for his portrait by his host, who was anxious to add the Königsberg celebrity to his collection. The resulting picture, which must have portrayed Kant at the age of fourty-four, is now hanging on the walls of Messrs. Gräfe and Munzer’s establishment at Königsberg.

Kant’s fame was now no longer confined to his native province or country, but was rapidly spreading into other parts of Germany. In 1769 he received the offer of the vacant chair of logic and metaphysics in the university of Erlangen, a post he seems at first to have been inclined to accept, much to the satisfaction of the students of the university. The position was not unremunerative according to the ideas of the time, consisting of 500 florins salary yearly, in addition to a liberal supply of fuel for the winter, with an immediate advance of 150 gulden for travelling expenses. The project seems to have been pending for some months, but was eventually abandoned. The same result attended an offer of the professorate at Jena, made in January 1770. Kant had finally determined not to leave his native town, let the allurements be what they might. The time was drawing near when the post which was the goal of his professional hopes was to become once more accessible. In the March of the same year (1770) the professorship of mathematics, becoming vacant, was offered to Kant. Singularly enough, Kant’s former successful rival, Professor Buck, had, immediately on learning the death of its late occupant, himself taken steps toward getting nominated for it, in lieu of the post he then occupied. The matter was thus easily adjusted. Buck resigned the chair of logic and metaphysics, while Kant relinquished his claims to that of mathematics. The two men were thus mutually installed in the positions of their choice; the ministerial rescript appointing Kant as ordinary professor of logic and metaphysics in the university of Königsberg, bearing the date of March 31st. The salary was 400 thalers (£60), besides lecture fees. Kant did not formally enter upon his duties till August 20th, 1770, when according to precedent he publicly defended his treatise De mundo sensibili, containing the fundamental theses of the ‘Critique.’ He chose as his respondent, his friend and pupil Dr. Marcus Herz, who a few days later returned to Berlin. With his assumption of the professorial robes commenced the middle period of Kant’s academical and literary life, when his system was elaborated and matured, and his powers were at the height of their activity. Henceforth we have the critical Kant before us.

Kant’s entry upon his new functions was almost coincident with the assumption of the entire educational departments of the ministry at Berlin by Baron von Zedlitz, a man of considerable culture and a zealous disciple of the Aufklarung, who at once recognised Kant’s genius and importance for the university, and remained an influential friend to him until his resignation eighteen years later. Zedlitz was no sooner in office than he issued a rescript proscribing the Crusian philosophy, making a clear sweep of the antiquated text-books previously in use, and generally calculated to put academic bodies “on their mettle.” No opportunity was lost of showing ministerial esteem for the occupant of the philosophical chair at Königsberg. In 1778 Professor Meier of Halle dying, Zedlitz immediately offered the appointment (which was of considerably greater pecuniary value than the one at Königsberg) to Kant, and was much surprised at its being declined by him. His anxiety for Kant’s worldy prospects was sufficient to induce him to repeat this invitation. “I cannot,” he writes, “give up my desire to see you remove to Halle. It is too bad that your way of thinking so exactly coincides with your post. Really, my dear Herr Kant, however praiseworthy this may be in itself, it does not seem to me well that you should so deliberately refuse a better position.” This second letter contained every possible argument, even to considerations of climate, but all to no purpose. Kant was inflexible in his resolution to remain true to his native town, by letting it have all the honour and advantages accruing from his genius. That the incident contributed, if anything, to enhance the minister’s esteem goes without saying. Departing from his usual practice of not dedicating his works, Kant inscribed the first edition of his ‘Critique’ to his “protector” Freiherr von Zedlitz. The expression “protector,” was in this case no mere form, as Kant found to his cost on the death of the free-thinking Frederick the Great many years later, and consequent resignation of his minister, which not long after followed, for his successor was a man of very different mould; it was under his administration that Kant, as we shall presently see, was first made to feel the existence of a press censorship.

Throughout the tenure of his office of professor, every morning, summer and winter, during the terms, saw Kant at his desk in the lecture-room at seven o’clock punctually, the lecture lasting two hours. His special lectures he was now obliged to give up, owing to the pressure of literary work. But besides those on logic and metaphysics, he had to deliver regular courses on ethics, natural theology, anthropology and physical geography, all of which were attended by literally “overflowing” audiences not alone consisting of students, but composed of men of mature years, from among all classes of the outside public. As time went on, the bulky manuscript originally employed grew smaller and smaller, till at last it dwindled to a piece of note paper, on which were jotted a few memoranda. His delivery is described as much more readily comprehensible, even on subjects in themselves obscure, than the literary style of the later works. Kant, when reproached with the clumsiness and obscurity of the latter, used to excuse himself by the reply, that they were only written for professional thinkers; that a special terminology had the advantage of brevity, and that, besides this, he liked to flatter the vanity of the reader now and again with obscurities and misunderstandings to give him the opportunity of exercising his wits upon them; it was otherwise in oral discourse, the object of which was to introduce the hearer to the subject. Kant’s logic lectures were less designed to expound a completed science than to teach his hearers how to think for themselves. With him formal logic was a means rather than the end it is with many academical exponents of the subject. In his philosophical lectures Kant had the habit of following his main idea into side issues, often at such length and in such detail as to be in danger of losing sight of it altogether. on these occasions, he would suddenly break off from his digression with the words, “In short, gentlemen,” and thus regain, as quickly as possible, the main thread of the argument. His naturally weak voice prevented his being heard at the farther end of the room with distinctness, while the slightest noise rendered him completely inaudible. But the respect, almost amounting to reverence, universally surrounding him, secured a breathless silence the moment he appeared at the lecture-desk, before which he was accustomed to sit while speaking. He had a habit, on commencing, of fixing his eye on some individual immediately in front of him, in order to read, by the expression of the face, whether he was being understood. This, sometimes, had unfortunate consequences, as any marked peculiarity in person or in dress, was apt, by involuntarily engrossing his attention, to completely disturb the current of his ideas. Jachmann relates, that on one occasion he entirely lost himself, owing to a missing button on the coat of one of his audience. His eye and thoughts were alike irresistibly drawn to this defect. The same thing occurred if an imperfection in the teeth caught his attention, an unusually open shirt front, or any exceptional “cut” of coat.

As dean of the university, a post he several times occupied, Kant had the reputation of being a strict examiner, but he never demanded more of students than the state of education in the higher schools admitted of. Jachmann amused Kant in after years, by describing the anxiety of himself and his teachers lest he should fail in passing the ordeal, especially as he had been trained in the antiquated Crusian philosophy. But, as Jachmann observes, Kant was too much a philosopher himself, to make any given system of philosophy the basis of examination. The functions involved in the rectorate of the university, which office he filled for the first time in 1786, the year of the death of Frederick II., he exercised “with dignity, without oppressive severity.” His views of academic discipline were of the most liberal nature, and he was never harsh on the minor irregularities incidental to student life. He expressed a disbelief in hothouse training, and his conviction of the desirability of considerable latitude being permitted for the individual character to expand itself. In short, he was, throughout his official career, beloved by the students, whom he treated with an almost paternal tenderness and interest.

On an increased grant being made to the university, Kant, of course, received his share in common with the other professors in the shape of an improved stipend. But a special and almost unparalleled favour was shown in his case by an addition of 220 thalers from the central state funds. Kant’s correspondence with Marcus Herz attests his prodigious literary fertility during this period. Dr. Herz was a favourite pupil of Kant’s, and one of the first public exponents of his system, which he introduced to the Berliners before the ‘Critique’ itself had appeared. The correspondence between the two men was kept up for many years, and only collapsed finally, owing to the extended medical practice of Herz, absorbing time and energies previously devoted to philosophical studies. The letters to Reinhold also illustrate the nature and extent of Kant’s work towards the close of this period. The old friendship or acquaintance with Hamann, for some time interrupted, was renewed in 1780, about which time Kant seems to have revised a translation of Hume’s ‘Dialogues concerning Natural Religion,’ which Hamann had made, while Hamann undertook to negotiate for the publication of the ‘Critique.’ The latter writes to Herder under date April 8th, 1781, “The day before yesterday I received the first thirty sheets of the ‘Critique of Pure Reason,’ but I had the strength of mind to resist looking at any of it till the following day. Yesterday I remained all day at home, and swallowed the whole thirty sheets at a gulp. . . . It seems to me to be tolerably free from printers’ errors, though my eye caught sight of a dozen or so. According to all human probabilities it will create an excitement, give occasion to new investigations, revisions, &c. But in the end, very few readers will be equal to the scholastic nature of its contents. It increases in interest as you go on, and there are fresh and charming oases, after one has been wading in the sand for a long time. Altogether, the work is rich in prospects and leaven to new decoctions whether within or outside the faculty.” And again, “On May 8th, on Sunday, I received eighteen sheets from Kant, but it is not yet finished, and will hardly be so in ten sheets more.” Finally on August 5th, he writes, “A week ago to-day, I received a bound copy from Kant. on the 5th of July I sketched a criticism en gros, but have put it aside, because I do not care to offend the author, he being an old friend, and I might almost say benefactor, seeing that I owe my first post entirely to him; but should my translation of Hume see the light ever, I shall hold no leaf before my mouth, but shall say what I think. Kant has the intention of bringing out a popular abstract of his work.” The popular abstract referred to was the Prolegomena. Hartknoch, the original publisher of the ‘Critique,’ expressed the wish to undertake the latter work, and received, through Hamann, a reply from Kant, accepting his offer, but intimating at the same time that, as far as his other writings were concerned, he could not pass over the local booksellers, of whose shops he made such extensive use. This resolution he adhered to, and, in spite of the pressing offers of other firms, gave almost all his subsequent works into the hands of Nicolovius, a young bookseller of Königsberg. Hamann, who, during the publication of the Prolegomena, seems once more to have quarrelled with Kant, exhibited nevertheless considerable interest in its progress, making repeated inquiries of Hartknoch on the subject.

The adverse criticism of Herder’s ‘Ideas to a Philosophy of History of Mankind’ excited considerable attention at the time it was written. There was published in the Deutsche Mercur, a bitter reply, curiously enough by Reinhold, subsequently Kant’s most ardent disciple, which elicited a rejoinder from Kant even more severe than the original criticism. In 1785 appeared the ‘Metaphysic of Ethics,’ the first edition of which was sold out in a few months, and a second, almost unaltered, issued early in 1786. Towards the end of the same year, we find Kant studying Jacobi’s recently published ‘Letters to Moses Mendelssohn on the Doctrines of Spinoza.’ Hamann says Kant could never make anything of Spinoza, though he had many long conversations on the subject with his intimate friend Kraus. In a letter of a few weeks later to Jacobi, he writes, “Kraus told me, that Kant had the intention to refute Mendelssohn, and make the first onslaught in a polemic against him. He confessed, notwithstanding, that with himself, as with Mendelssohn, your exposition was just as incomprehensible as the text of Spinoza.” Hamann’s letter to Jacobi of Nov. 20th contains the important statement (if it is to be relied on) that “Kant confessed to me, that he had never properly studied Spinoza, and that, being taken up with his own system, he had neither the desire nor the time to enter into others.” Shortly after, we hear from the same source, that the notion of refuting Mendelssohn had been given up, but that Hamann was going to do all in his power to induce Kant to reconsider this decision, when the death of Mendelssohn, shortly after, terminated the matter. Kant’s admiration for Mendelssohn’s style was very great; indeed his estimate of the Jewish writer’s genius seems to have been somewhat exaggerated. It is probable that they never came personally into contact, but several letters passed between the two thinkers.

Kant’s academic fame was now (1786) at its height. Places had to be taken at least an hour before the commencement of the lecture, so great was the “rush.” I must not omit to mention an important change in our philosopher’s mode of life, which took place a little while before this time. In 1783 he had purchased the house which he retained till death. It was situated in the centre of the town, and may still be seen, bearing, on a marble tablet, the inscription, “Immanuel Kant lived and taught here from 1783 till the 12th of February 1804.” A few years later, he established a ménage of his own. It is almost needless to say this was of the greatest simplicity, Kant’s abhorrence to the least appearance of ostentation being proverbial. From this time he regularly invited a few friends to dine with him every day, with the exception of Sunday, when he dined at the house of the English merchant, Motherby. He could not entertain more than six persons at the table, as his dinner-service only accommodated that number. Among the friends invited, one of the most constant was Professor Kraus. Kraus was also a frequent companion of Kant in his daily constitutional walks. Kant often intimated to various members of his acquaintance that he regarded Kraus as one of the greatest intellects the world had ever produced. “Of all the men I have ever known in my life,” he used to say, “I have found none with such a talent for comprehending everything, and learning everything, and yet for excelling, and distinguishing himself in everything, as our Professor Kraus. He is quite a unique man.” Kraus, on his side, denied himself his single relaxation, a summer trip to the country residence of his friend Auerswald, in order to spend the vacations with his old teacher Kant. This friendship with Kraus lasted uninterruptedly till the death of Kant, although latterly, for various reasons, the two men saw each other less frequently than at the period of which we are speaking.

Another of Kant’s “table-companions” was Hippel, a man of tremendous conversational powers, and of varied culture. His intimacy with Hippel was not of the same nature as that with Kraus, being chiefly limited to mutual invitations to dinner, but the acquaintance thus far continued without any noteworthy breach till Hippel’s death in 1796. Two letters of Kant to Hippel are preserved, which are not uninteresting, one as exhibiting the humorous side to Kant’s character, and the other his good nature. Hippel, it should be premised, at the time, held the office of Chief Burgomaster, police-director, and inspector of the city prison. The first letter, dated July 9th, 1784, runs as follows: “Your excellency was so good as to desire to remove the grievance of the inhabitants of the Schlossgarten, with regard to the stentorian tones of the hypocrites in gaol. I do not think they would have cause to complain that their souls’ salvation was in danger, if their voices were moderated in singing, so far that they might be heard with closed windows, without having to exhaust themselves by shrieking. The testimony of the warder, with which it seems you are chiefly concerned, as to their being a God-fearing folk, you might have, notwithstanding, for he would still be able to hear them, and after all, their tones would only be lowered to the point which the pious burghers of our good town find adequate to their edification, in their own houses. one word to the warder, if you will send for him, and order him to make the above a fixed rule, will suffice to put a stop to this nuisance for once and for all, and remove an annoyance from him, whose peace you have been good enough to promote on more occasions than one, and who will always remain, with the deepest respect, your most obedient servant, I. Kant.”

The second letter, dated the 29th of September, 1786, commences with a compliment on a title being conferred on its destined recipient, but the real object is to petition for the continuance of the stipend of a young student: “Your excellency, accept my sincere congratulations on the well-merited distinction appended to your name, which, although it can add nothing to your already well-established public recognition, is a pledge that you will meet with less opposition in your purpose of doing good, the only interest I know which you have at heart. Permit me, in accordance with your good nature, now to bring before you a little matter connected with the University. Herr Jachmann, the elder, has informed me that the stipend he has hitherto enjoyed by your forethought, terminates this next Michaelmas. As he is now zealously devoting himself to his medical studies, and can thus afford no time for the private teaching necessary to his subsistence, he earnestly begs you to have the goodness to allow him one of the stipends announced in the ‘Intelligencer.’ Should you permit him, either personally or by writing, to make this application to you, please to give me a hint of the same. This act of goodness will always profit a brave, thoughtful, and talented young man: so much I can vouch for. I remain, with respect and affection, yours ever, I. Kant.”

We have now reached the period when Kant had become the central figure in the intellectual world of Germany. The ‘Critique of Practical Reason’ appeared in 1788, and the ‘Critique of Judgment’ in 1790. The critical philosophy, now complete, was being taught in every important university throughout every German-speaking country, irrespective of creed. Men of science, no less than philosophers, were attracted to it on all sides. Professors and savants made pilgrimages to Königsberg from the most distant places—Berlin, Jena, Heidelberg, Wurzburg, and even Vienna—to visit the philosophic Jupiter of the Baltic town, and seek elucidation on obscure points in the ‘Critique.’

When it is remembered that at the period in question not merely were railroads undreamt of, but even good roads all but unknown in central Europe, the enthusiasm and determination which led to journeys being undertaken involving the expense and fatigue these must have done, will be fully realised. Sometimes, it is true, the cost was defrayed by the prince or grand-duke of the State in which some prominent university was situated, but such cases were exceptional.

It would hardly be rash to say that no single book has ever achieved a success at once so rapid and lasting as the ‘Critique of Pure Reason.’ Although just at first it failed to attract much notice, within ten years of its publication it occupied the position of a classic. For such an effect to be produced by a philosophic work, written without any regard to style whatever, is a unique fact in the history of culture. A new light had, as Schiller expressed it, been lighted for men.

“Many regarded Kant as the prophet of a new religion, and Reinhold declared that, ‘in a hundred years Kant would have the reputation of Jesus Christ.’ The Jena Allgemeine Literatur Zeitung proclaimed a novus ordo rerum. In the course of some ten years 300 attacks and defences of Kant’s philosophy appeared. The enthusiasm aroused the hatred of opponents. Herder characterised the whole movement as a St. Vitus’s dance, while fanatical priests sought to degrade the name of the sage of Königsberg to a dog’s name. We must not alone be acquainted with the books written from a more or less impartial standpoint, but also with the subjectively coloured pamphlets and letters belonging to the period, to form an adequate idea of the, at present, almost inconceivable commotion. The powerful impression of the Kantian philosophy on all classes in the nation, implied a corresponding influence on every sphere of intellectual activity. Theology, jurisprudence, philology, even natural science and medicine were soon drawn into the movement, quite apart, of course, from the special philosophical disciplines which were subjected to its mighty influence.* ”

The critical movement, at first confined to Germany, was not long in spreading over Europe. Nitsch, a pupil of Kant, appeared in London in February, 1794, with a prospectus bearing the psychologically coloured heading, ‘Proposals for a course of lectures on the perceptive and reasoning faculties of the mind, according to the principles of Professor Kant.’ In this prospectus he offered to deliver three lectures, admission gratis, and at the close of each to defend the principles enunciated against all comers. on the evening of the 3rd of March, the occasion of the first lecture, the street in which the lectureroom was situated was early lined with carriages, and Nitsch, on his appearance on the platform, found himself confronted by a large audience, composed of members of the nobility, the clergy, and the “learned” professions generally, and including, as we are informed, many “richly attired” ladies. The lecture lasted an hour and a half, and was received with applause, but Nitsch had no sooner concluded than he was forced to commence a disputation, lasting two hours, in the course of which he was required to answer every conceivable objection that could be raised in a running fire of questions. So successfully did he pass through this ordeal, and so much interest did the three introductory lectures evoke, that a sufficiently large number of subscribers was got together to make it worth while for him to undertake a course of thirty-six lectures, at a fee of three guineas each person, expounding in detail the principles of the critical philosophy. He concluded them in August. But, meanwhile, the desire for further information had become so great, that a repetition of the lectures was commenced the following October, and a subscription raised for their subsequent publication.

The success of Nitsch in his introduction of “criticism” into England is certainly somewhat surprising, when we consider the newness of the doctrine, and the conservative nature of English thought. It is difficult to conceive that his hearers, accustomed as they were to a treatment of philosophical questions so alien to that of Kant, really comprehended the full bearings of the new system.

The next representative of Kant’s principles in this country, was John Richardson, who studied philosophy in Halle under Beck, and on his return to England published a translation of the ‘Prolegomena,’ and some other short pieces. Richardson admits, in his preface, that he had found the transition from empiricism to critical idealism very difficult, notwithstanding his having had the advantage of a German university education.

In France, where the Revolution was at its height (the Revolution which was the deathblow of the material structure of ages, as Kant’s philosophy was of the intellectual structure of ages), and communication with central Europe was interrupted for some time, except the pièce d’occasion entitled, ‘Everlasting Peace,’ translated in 1795, little was known of Kant beyond the fact that he was the head of a great intellectual movement in Germany, till, in 1798, the recently established Institut Nationale ordered a report of the new doctrine to be laid before it. In the following year (1799), Kant’s first French disciple, Charles François Dominique de Villers, published at Metz an abstract of the ‘Critique,’ and, a year or two later, another treatise, entitled La philosophie de Kant, ou principes fondamentaux de la philosophie transcendentale.

Among the other Latin nationalities, Kant remained little more than a name till some years after his death, and the same may be said of the Slav countries of Eastern Europe. In the Netherlands, on the contrary, in 1796, an elaborate work in four volumes, ‘De Beginzels der Kantiaansche Wysgeerte,’ was published, in which, notwithstanding its modest title, critical principles were exhaustively expounded, while in October 1798 a new magazine, the ‘Kritische Magazin,’ was founded for the express purpose of propagating and defending the principles of the new philosophy.

Among the numerous pilgrims to Königsberg, one of the most interesting, if not from any special eminence, from the probably unique enthusiasm Kant inspired in him, was the Berlin physician Erhard, who arrived in Königsberg about the same time as Fichte. “All pleasure that I have ever had in my life,” he writes in his autobiography, “is as nothing against the thrill sent throughout my whole soul by several passages in the ‘Critique of Practical Reason.’ Tears of the highest rapture, how often have I not shed over this book? The very recollection, even now, of those happy days brings tears to my eyes.” And again, “Do I hold my own in the battle with the crushing thought with which the history of the time, like an evil demon, so often fills my soul—that the belief in the development of humanity in the whirl of human action, is an old wives’ fable, designed to restrain the child from wandering down the path of coarse pleasures, and an empty consolation for the jubilation of his comrades—do I withstand this soul-oppressing thought, then it is thy work, my teacher, my spiritual father.”

The last letter (April 16, 1800) of Erhard to Kant closes with the words, “Think of me as of a son who intensely loves and reverences him who brought him up, for you are even to me as my father, though him I have to thank that he left me prepared for your instruction.”

Among the eminent men, not professional philosophers, who, at this time (1790–1800), were zealous votaries of Kant, foremost stand Schiller, Wilhelm von Humboldt, and Jean Paul Friedrich Richter. The influence of Kant on Goethe was less marked, and probably in the main derived from Schiller. The ‘Critique of Pure Reason,’ he said, lay outside his sphere, though the ‘Critique of the Faculty of Judgment’ seemed to have interested him considerably. He admits that much in Kant’s thought he was unable to assimilate. How thoroughly, on the other hand, Schiller was imbued with Kantianism his works and letters testify. Wilhelm von Humboldt remarks in the ‘Introduction to his Correspondence with Schiller’ (published in 1830): “Kant undertook and completed the greatest work for which the philosophic reason has to thank any single man. He proved and sifted the whole of philosophic procedure, in a way that led him to encounter the philosophies of all times and all nations. . . He carried, in the true sense of the words, philosophy back into the human bosom. Every attribute of the great thinker he possessed in the fullest measure.” The whole of this introduction is masterly in its estimate of Kant’s work, but belonging as it does to a period long subsequent to the death of Kant, our only purpose in alluding to it here is, to show the impression left on the mind of Humboldt by the study of the ‘Critiques’ undertaken by him between thirty and forty years previously, and which is abundantly reflected in the correspondence itself.

The enthusiasm of Jean Paul is characteristically expressed in a letter to his friend, the Pastor Vogel: “For Heaven’s sake buy two books, Kant’s ‘Foundation to a Metaphysic of Ethics,’ and Kant’s ‘Critique of the Practical Reason.’ Kant is no mere light of the world, but a whole dazzling solar system at once.”

The bulk of Kant’s collected correspondence falls within these last twenty years of the century, the crowning period of his life. It comprises, amongst others, letters to and from Moses Mendelssohn, Marcus Herz, Reinhold, Schiller, and Fichte. As instances of Kant’s epistolary style, we quote letters to the two last-named, respectively.

Schiller had written, asking Kant to contribute to his newly-founded periodical, Die Horen, at the same time taking the opportunity of thanking him for a favourable review of his (Schiller’s) essay on ‘Grace and Dignity,’ and acknowledging his indebtedness to the critical philosophy. Kant replied nine months subsequently (Schiller’s letter is dated June 13th, 1794, and Kant’s, March 30th, 1795), as follows: “The acquaintance and literary intercourse of a learned and talented man like yourself cannot, my dear friend, be otherwise than desired by me to enter upon and cultivate. The plan for a new journal, communicated by you last summer, came duly to hand, also the two first numbers a short time ago. The letters on the ‘Æsthetic Education of Man,’ I find admirable, and shall study them in order to be able to communicate to you my ideas on the subject. The paper contained in the second number on the difference of sex in organic nature, I cannot decipher, although the writer seems a capable man. . . An idea of the kind flashes across one’s mind occasionally, but one does not know how to make anything of it. For instance, the natural arrangement that all impregnation in both of the organic kingdoms requires two sexes, in order to propagate its kind, is always astonishing, and opens up an abyss of thought for the human reason. If we are unwilling to assume providence to have chosen this arrangement, in a playful manner, as it were, to avoid monotony, but believe ourselves to have reason for regarding it as the only possible one, an infinite prospect lies before us, of which we can make simply nothing,* as little indeed as from what Milton’s angel tells Adam of the Creation: ‘Male light of distant suns mingles with female for ends unknown.’† I am concerned lest your journal should be prejudiced by the fact that your writers do not sign their articles, and thus make themselves responsible for their opinions, a point which interests the public very much.

“For this gift, then, I offer my best thanks, but as regards my small contribution, I must ask for a somewhat lengthy postponement, since political and religious matters are now under a certain embargo [referring to the stringent press censorship, of which more later on]. and beside these subjects, there are hardly any of interest for articles such as would commend themselves to the great reading world, at least at this moment; so we must watch for a change in the weather, and accommodate ourselves to the time. I beg you to give Herr Professor Fichte greetings and thanks for the many works from his pen which he has sent me. I would have done this myself if the variety of my labours, and the discomforts of old age had not compelled me to postpone it constantly. Kindly give my remembrances also to Herren Schultz and Hufeland.

“And now, dearest man, I wish your talents and good intentions adequate strength, health, and longevity, the friendship included, with which you honour him who is, with the greatest esteem your devoted and true servant, Immanuel Kant.”